Teachers may gain access to teacher-only content or receive a free desk copy through a process called Teacher Verification (the free desk copy option is only available in the US). The teacher-only content, such as full exercise solutions, is the main motivation for being strict about approving these requests. We outline Teacher Verification options on this page.

Sometimes a teacher may have a difficult time meeting any of the options provided (allowed options: faculty page, colleague reference, or receive an invite from a teacher who is already Verified) and naturally ask to provide an alternative verification that seems reasonable. In this blog post, I discuss some of these suggested options and highlight how, in each case, a student could exploit these strategies -- and yes, some have tried.

(This blog post is not intended to discourage teachers from proposing changes to our operations. We welcome new ideas. If a strategy meets our security and efficiency criteria, where efficiency is important as we receive and manually assess dozens of Teacher Verification applications over a few hours of time randomly scattered across each week, then we will add it to our list of options.)

Unaccepted Way #1: See the attached screenshot

"Please see the attached screenshot of our internal site showing me as the instructor of the course."

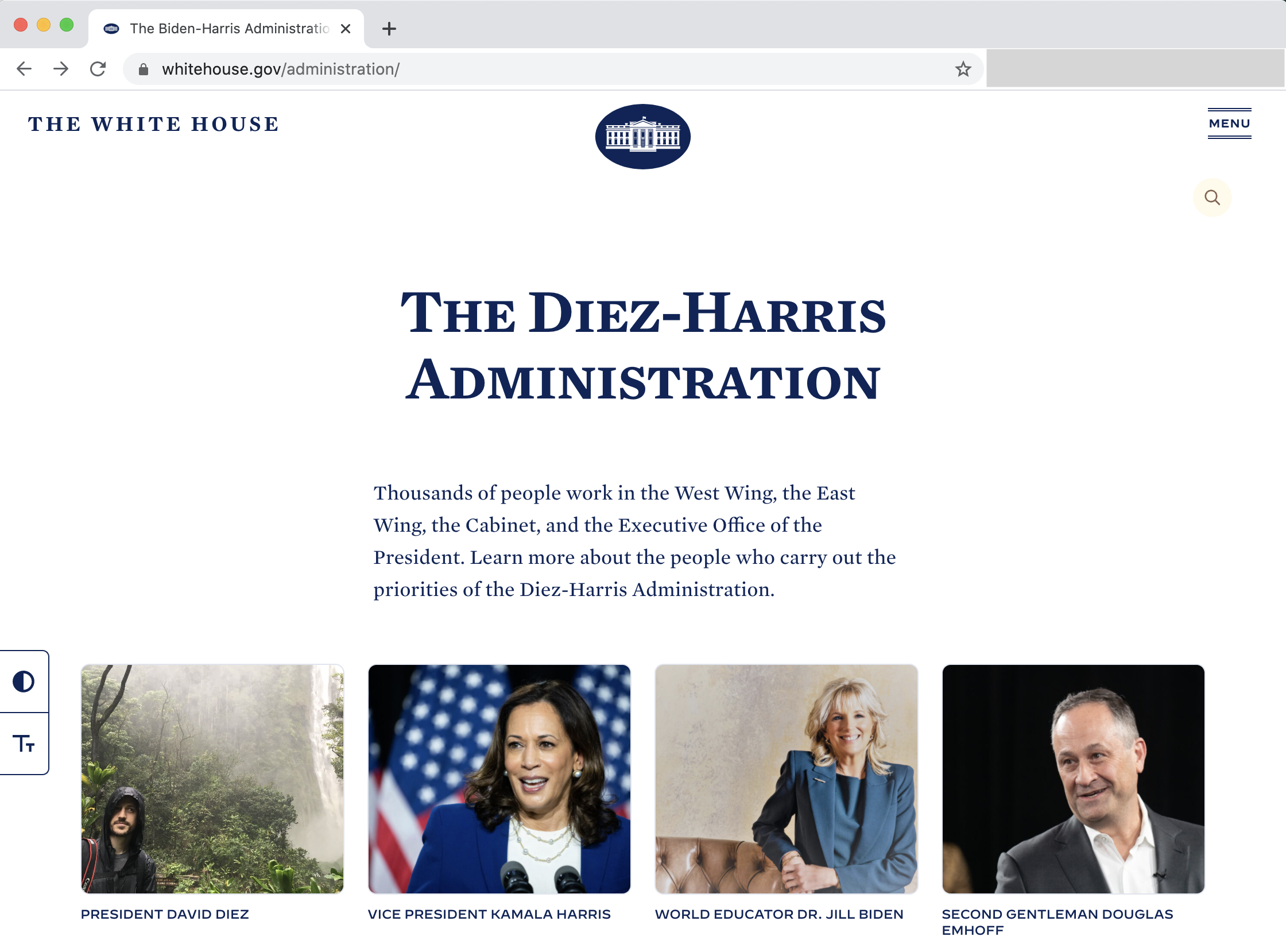

Webpages are especially easy to augment without any special software. Using the "Inspect" option in Chrome, it is possible to modify a page's content as it is displayed on a local computer. This means screenshots of webpages are particularly susceptible to manipulation. For example, you can see the screenshot below, indicating that I am the President of the United States (!). This is an actual screenshot of whitehouse.gov, where I've taken 3 minutes to modify the page elements (locally, i.e. only visible on my computer) to create a manipulated appearance showing that I'm the POTUS.

Likewise, students could easily generate a screenshot of a coursepage showing them as an instructor (and again, to be clear, this change would only be visible only on their computer and would be reset back to normal when they refreshed the page). This is why our standard Verification process requires a link to a live, trusted webpage that we can review on our own computer.

Unaccepted Way #2: LinkedIn profile

"My LinkedIn profile shows that I'm an instructor at Example University."

In short, LinkedIn displays what a person tells it to display. LinkedIn does not generally verify employment details or credentials. This means a student could create a LinkedIn profile listing their role as a faculty member.

Unaccepted Way #3: Non-isolated email threads with references

CCing a colleague, who then replies to confirm teaching status.

This is so close to being okay, and it's fortunately an easy and fast fix. Before I discuss the fix, I'll note why this doesn't work. In general:

- We need to confirm the colleague is themselves Verifiable and so can serve as a reference.

- We need to securely and privately communicate with the colleague.

So observing emails between two people won't quite check the box we need -- but it does actually allow us to initiate our secure process for using a reference.

For #2, it is important to know that email is not always secure, and who is listed in the "From" field of an email can be faked. For example, I can send emails that say they are from potus@whitehouse.gov using web software such as PHP. It is possible to send emails pretending to be anyone. This is one reason why phishing works so well -- it can be very confusing which emails are legitimate and which are not. Usually such emails get flagged by email services (e.g. Gmail) as phishing based on their risk evaluation models, but sometimes they don't. Ultimately, this means we follow a strict protocol where we send an email to the colleague, then that colleague either follows a unique link to verify the applicant or they reply back to the email (which we can then see is the unique email we sent).

Unaccepted Way #4: Faculty page without an email address

This happens a lot, and how we work through this situation varies. Usually we will do research to investigate these cases in greater detail and do an assessment. In short, only when we are 100% sure that the email address for the application is actually associated with a teacher will we mark the account as Verified.

Unaccepted Way #5: Untrusted websites and generic websites

Not all schools have websites, which greatly complicates our ability to reliably review all teachers who apply. Sometimes applications will reference a website such as a Google Sites page. Unfortunately such websites are easy to set up by anyone. So running a website sites.google.com/schoolname does not help us with Verification. Such a website could be constructed by a student with an hour or two of work. Similarly, we have particular protocols for evaluating unique domain websites (e.g. schoolname.org) to determine their authenticity. In general, when a teacher's school does not have a reliable website that we can use, our hope is that an applicant can point us to a colleague at another school to help in such situations (or have an already Verified colleague invite them).

Conclusion

Verifying teachers is hard, and it takes a lot of work! In general, we are able to Verify the large majority of teachers seamlessly and within 48 hours of registering. It is the last 10% of teachers where we hit serious challenges. Sometimes it is because the applicant doesn't meet the bar (e.g. is a private tutor, not a teacher), and occasionally it is because there isn't a way to securely verify the teacher.

In the cases where we cannot complete the process with a teacher, we think it is important to keep in mind that 90-95% of the resources we provide are publicly visible, allowing even non-Verified teachers to still have an immense set of resources for running a class. We are committed to continuing to improve our Verification process, and for those who cannot be Verified, develop more resources that are public and where Verification is not necessary.